The twists and plot turns of the enduring Freud legacy

British author Esther Freud has a complex lineage and she is returning Down Under to talk about that and her latest novel.

The young woman was standing on the side of an Irish country road, hitchhiking with three young children in tow. Looking for shelter, a commune, a shared house, some place that would take them in.

So begins Part One of Esther Freud’s new novel, Sisters and Other Lovers. Much of her work is based on her own life. She admits she takes “the seeds from my own life and then in an effort to make it a story it goes further and further from my life”.

But then you couldn’t make the components of her life up. Speaking by Zoom from her home in London, ahead of her Australian tour in August and after an early morning swim, she suddenly, endearingly, realises she has forgotten to brush her hair. She was one of the children of the revolution. Standing behind her mother sticking her thumb out.

“We hitched a lot when we were young. In the ’70s, people hitched all the time,” she explains.

“We hitched a lot when we were young. In the ’70s, people hitched all the time,” she explains.

With her lustrous ancestry, literary reputation and starry relatives you could be forgiven for thinking that Esther Freud has come from a privileged English background, posh schools and all that.

Her father was the great figurative painter Lucian Freud, her great-grandfather Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Her uncle Clement Freud was an English raconteur, chef, soldier, MP, journalist and showman. Her sister Bella is a noted British fashion designer. Various other Freuds have distinguished themselves in the media and arts.

But her childhood was far from the London cultural elite. Her mother Bernadine Coverley, escaping a conservative Catholic family, found herself in Bohemian London and pregnant at 18. By the time Esther was born two years later Bernadine’s relationship with Lucian was disintegrating and she hit the hippie trail, setting off to Morocco with a group of friends in a van.

That profound time of “light and joy and freedom” in Morocco would become Esther’s first novel, Hideous Kinky, which was made into a film starring a young Kate Winslet. There have since been eight books, some of them semi-autobiographical, all dealing with relationships, complex family dynamics, identity.

You might like

I Couldn’t Love You More (2021) was a reimagining of her parents’ relationship. It was a peripatetic childhood with a liberated hippy woman.

“We were living at times in a very sort of impoverished way. Not having anywhere to live, we’d have cheese on toast for supper.”

But it was colourful and has provided a lifetime of material for a writer.

“I felt I lived in at least two different worlds, which is very useful,” she says.

Esther would visit her father in London – “if you were 10 and he liked you he would talk to you”.

Lucian Freud was a glamorous figure in his silk scarves, exquisite clothes, even though he dressed in “rags” when he was painting. She later realised that he taught her “how to choose language in the most eloquent and exquisite way that was possible”.

“He had very strong opinions about words and phrases. He loved a feud, so he was quite often sitting at his kitchen table with a pencil trying to work out the most devastating response to someone he wanted to annihilate. He would write and write drafts, then try it out and he’d be laughing. So it showed me the power of language.”

She would often pose for him through her teens and 20s. Watching him work was a valuable lesson in keeping going when “you’re literally wading through sludge”.

She saw that “when things weren’t going well, he didn’t give up. He just worked on. And suddenly something would go well and the air in the room would actually change and you would sort of be pulled in, almost like into a vortex. I would stay completely silent, as still as I could, trying to kind of keep the air in with the same amount of magic and tension.”

He was, she says, “a beautiful man”, a fact not lost on his many, many lovers. He acknowledged 15 children.

Subscribe for updates

‘I have had a lot of experience of meeting people who are related quite closely to me, quite out of the blue’

One of the str’ongest scenes in My Sister and Other Lovers is meeting three half-brothers who look unambiguously like him. The protagonist and her sister tell their father about their existence: ‘Their mother. Helen. She lived near.’ He nodded, neither in agreement nor dispute. ‘Three of them?’ He poured water, gulped it down. ‘I did occasionally drop by.’

Now, Esther admits, “yes, I have had a lot of experience of meeting people who are related quite closely to me, quite out of the blue.”

When she met him for lunch, Lucian would suddenly announce “we’re meeting some of your sisters”. “As if it was nothing to do with him and only to do with me, as if I somehow had conjured up these possibly inconvenient sisters.”

Artists often have to be monumentally selfish and focused. They can leave a trail of broken women and children. Esther says her parents stayed friends until the end of their lives because her mother had the strength to make a complete break from him. She was never, like others, “hanging on his words of favours, waiting”.

Having a giant of a father, she says she saw men as “either Gods or sort of retards”. “I didn’t realise that they could just be delightful people who could fit in between.” Having two sons taught her that.

‘I don’t think writing is therapy but it is very therapeutic’

But she has realised that she has always chosen men who put work first. In her book, a marriage has a long slow death, because “he just avoids and avoids until when he loses all faith in it and gives up. And I guess that is something I’ve experienced with men in my life”. Her marriage to the actor David Morrisey ended in 2020.

It must be somewhat daunting for a psychoanalyst to have Sigmund Freud’s great-granddaughter as a patient. In Sisters and Other Lovers the narrator Lucy experiences transference in psychotherapy. Esther says now that she couldn’t really examine and look at what is behind things in her work without it.

“I don’t think writing is therapy but it is very therapeutic,” she says. “The therapy probably needs to have happened first to have some insight into it, because there is nothing worse than a book that is a grudge. Without the therapy and without the clarity that is what a book can become. I haven’t ever written a memoir because I’m not interested in telling the truth. I’m interested in weaving a story out of something that has truth behind it.”

One wonders, though, what Sigmund would have made of his grandson, Lucian, his proliferate sex life and his immoderate number of children.

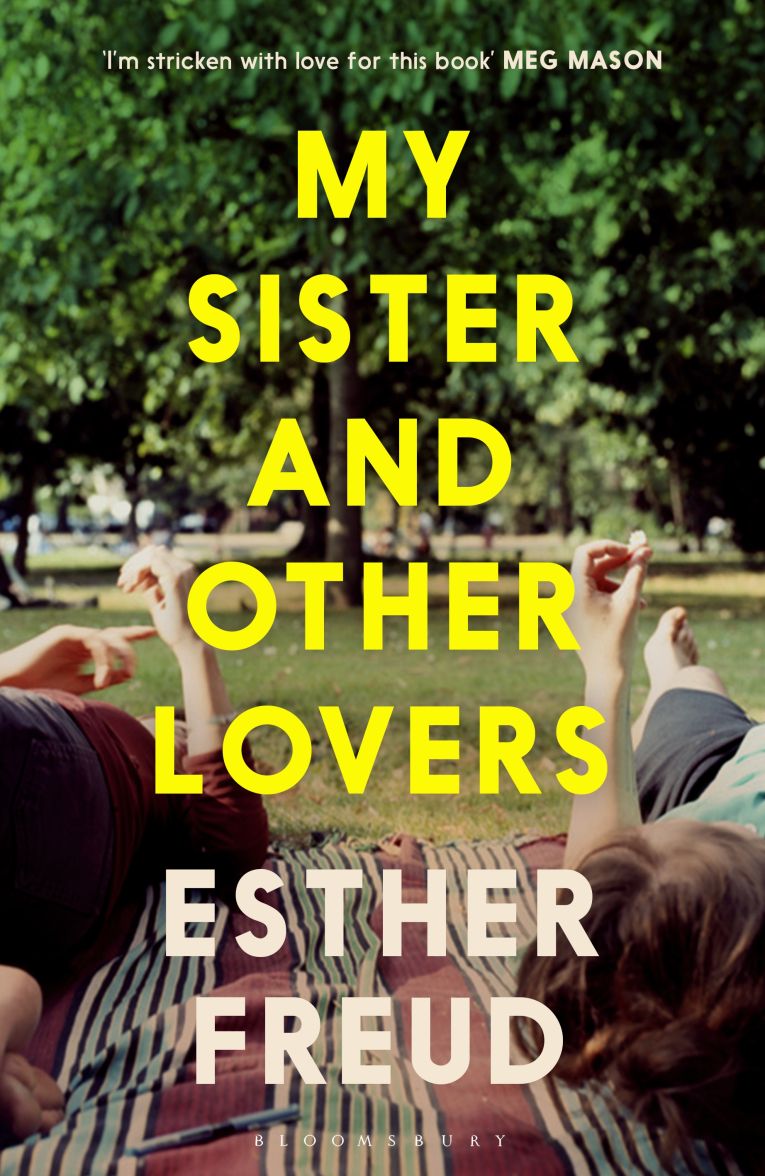

My Sister and Other Lovers by Esther Freud, Bloomsbury Publishing, $32.99, is out on July 1, with eBook and audio also available.

Esther Freud will be at a Brisbane Writers Festival special event at Brisbane Powerhouse on August 6: brisbanepowerhouse.org/events/esther-freud

She will also be a guest at Byron Writers Festival on August 8: byronwritersfestival.com

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence