Life lessons and the finals’ cut at the Archibald

In his latest book Bold, Brave and a Bit Quirky artist and architect Paul Fairweather muses on life lessons and that time he entered the Archibald Prize and unexpectedly made the finalists list.

In 2000 my closest friend Michael died at the tender age of 39. Michael was a luminary in the Australian contemporary art world. His death, when I was 40, gave me pause to reflect on my life, particularly the things that I had been procrastinating about for years.

The first thing I did was to make a list and ask myself why I had delayed. The answer I came up with was that the things I procrastinated about most were things I feared – that I would be a failure.

Looking back, it struck me how often fear sits quietly behind procrastination, pulling the strings. I wasn’t putting things off because I didn’t care or didn’t have time. I was avoiding the possibility of failing, of not being good enough. It’s a sneaky thing, fear. It dresses itself up as busyness or distraction but, really, it’s just keeping us safe and small. Standing here in the middle of my grief, the realisation hit: If I wanted to honour Michael, I had to stop letting fear run the show.

The top three items on my list were to walk the Kokoda Track, to learn to play an instrument and to enter the Archibald Prize. Later that year, I walked the Kokoda Track, bought my brother-in-law’s saxophone, joined a late-starters’ band and started a project to draw two portraits a day – one of myself and one of a friend or family member.

You might like

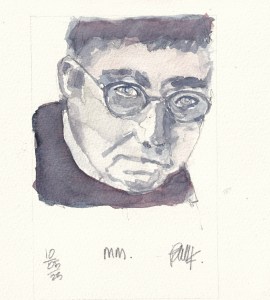

Then, I decided to enter the Archibald Prize and set about choosing who to paint. I wanted to do a painting of Michael, but the rules require that you complete at least one live sitting, which was not possible. So, I devised a plan to paint a portrait of an artist Michael had represented as he read The Australian, showing the half-page black-and-white photo in Michael’s obituary. It was titled Exhibitor of Exuberance.

The subject I inquired about was the artistically named Mostyn Bramley-Moore who, besides being a contemporary artist, was also the head of the Queensland College of Art at the time. To my surprise, he said yes.

One of my challenges was that I was both an architect and an artist, but not the sort of cutting-edge contemporary artist Michael exhibited. Art snobs would have called me a decorative artist on a good day. I am essentially self-taught as a painter, but during one of the sittings with Mostyn, he gave me some tips on how I might paint his glasses. So, I should say self-taught except for the tuition I received from the head of the Queensland College of Art.

There were nearly 1000 entries in the year I submitted my portrait, and they selected 31. I am not sure who was more surprised, Mostyn or me, that I was chosen as one of the 31.

Subscribe for updates

But it was a bittersweet moment. The sadness of losing Michael motivated me to confront my fears and incorporate him into my work. Then, because I faced my fears, I was recognised for the effort. There was another surprising aspect to this experience that I had yet to discover. One of the board of trustees on the judging panel was Michael’s old business partner, whom I knew. Let’s call him Bill because that is his name.

After the announcement of the winner (spoiler alert: not me), he informed me that he had advocated strongly for me. I was taken aback and felt that I had somehow cheated my way in. Even being selected as a finalist for the Archibald Prize couldn’t convince me I was a “real” painter. My goal had been to enter – to have a go, to get something finished and submitted. And here I was, actually hanging on the wall next to some of the country’s most celebrated artists. It didn’t compute. That old inner voice – the one that says you’re not good enough, you don’t belong here — made sure it got a say. Our self-doubt has a way of showing up just when we think we’ve outrun it.

Learning to keep going despite it – to keep painting, showing up, sharing – that’s been a lifelong lesson. Recognition is nice, sure. But trusting yourself? That’s the real prize. That said, I was disappointed not to win. In kindness, Bill noted three things to me that alleviated my disappointment.

Firstly, he pointed out that during that period the Archibald Prize was highly nepotistic, with the same Sydney and Melbourne artists exhibiting yearly as either artists or subjects, about 80 per cent of the time. Rarely did anyone north of the border get a look in. And the subject was as important as the artist, and Michael was an iconic figure in the Australian art world.

Secondly, if it weren’t a good painting, it would never have been selected. Lastly, he said that if I had never completed the work, it would never have been considered. You have to be in it to win it.

This is an edited extract of Chapter 24, Archibald, from Bold, Brave and a Bit Quirky by Paul Fairweather, AndAlso Books, $30.

andalsobooks.com/#/bold-brave-and-a-bit-quirky

Paul Fairweather is a speaker, writer, artist, podcaster and unapologetic experimenter. Co-founder of the award-winning Fairweather Proberts Architects, he now helps people connect and communicate through ideas, stories and bold thinking. His book is part-memoir, part-manifesto and a mischievous nudge to anyone who’s ever had an idea they felt too scared – or too busy – to bring to life.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence