What have the Romans ever done for us? Eh?

A book full of astonishing facts and strange stories drawn from Ancient Greece and Rome – rarely retold in English – is a surprise and a delight.

Bushfires, flash floods, fireworks – actual and metaphorical. Stabbings in broad daylight, shark attacks. Is there nothing new under the summer sun?

This year there is – a collection of startling anecdotes fresh from the printer (though it’s taken three millennia to recycle some of them).

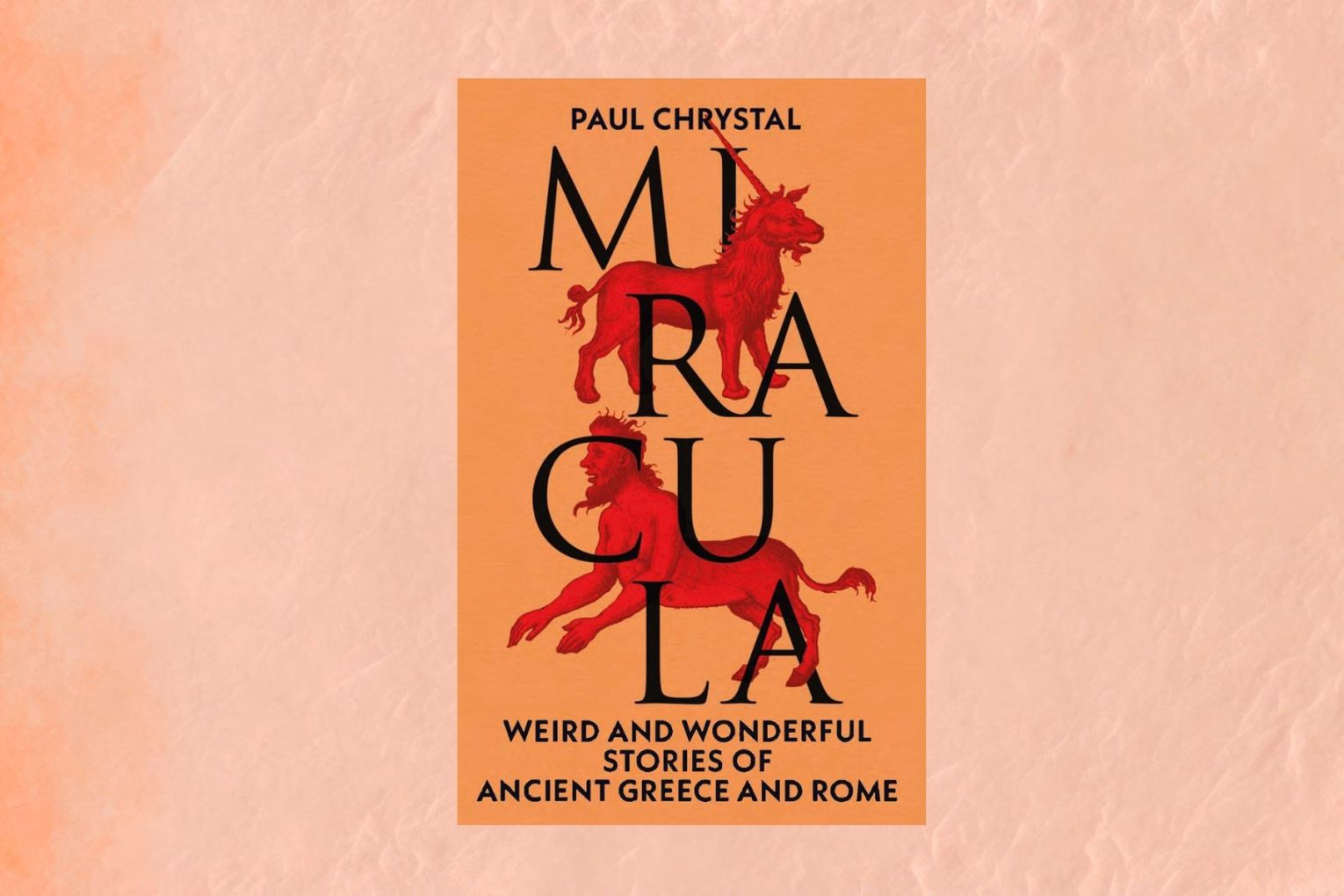

English broadcaster and bookshop owner Paul Chrystal has upended the paradigm of sober history-telling to produce a potpourri of stranger things (now there’s an idea) in his new book, Miracula: Weird and Wonderful Stories of Ancient Greece and Rome. And in doing so, he has given us two lessons.

First, that the human capacity for committing and relishing freakish events is not confined to one historical era. Second, that we seem to have an inexhaustible relish for misfortunes – provided they befall others.

Here’s an example of what’s “new” from Chrystal’s book. Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor whose postmodern afterlife has reinvented him as an esoteric sage, was one of history’s most prolific serial killers.

You might like

Chrystal explains: “He can put his hand up to six million deaths brought about by his inadvertent introduction of smallpox into the Mediterranean population, imported after a campaign in AD165 in the East. The pandemic raged for 25 years and Marcus Aurelius succumbed, himself, along with 10 per cent of the population of the empire: poetic justice?”

Chrystal’s canvas is populated with many other snippets of previously obscure knowledge that he tells us are in his book in English for the first time. Take the term Battle of Gaza. Most readers would immediately think of the ongoing conflict that erupted there in 2023. While students of Australian history might recall two campaigns there in early 1917, the second of them involving the Anzac Mounted Division in one of the last military actions conducted on horseback.

Yet it’s quite another thing to ancient history buffs. Fought in 217BC near modern Rafah, between Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy IV Philopator and the Seleucid Empire’s Antiochus III, it was one of the biggest of ancient battles, involving 6000 cavalry and 102 elephants. And it is the only battle we know of in which African and Asian elephants were used.

For a salutary reminder that Groucho Marx didn’t invent the one-liner, we have this from the 5th Century BC’s Greek tragedian Euripides, showing his inventiveness could also take a comic turn: “A mother’s love is always stronger than a father’s; for she knows the children are hers: he only thinks they are his.”

Chrystal’s humorous tales will chime with diverse senses of humour

And, for a witty response to a mundane inquiry, this – from 1st Century Roman writer Plutarch – is hard to beat: “A loquacious barber asked King Archelaus of Sparta how he’d like his hair cut. He replied: ‘In silence’.”

Subscribe for updates

If there’s an irritating summer blowfly in the author’s soothing ointment, it’s his predilection for words so arcane (definition: understood by few) that his readers risk being distracted from the subject matter at hand and denied full enjoyment of his rich tray of offerings. To write for a general audience and then baffle them with the likes of oleoculture, phreatic, anaphora and teichoscopy, is remiss.

Occasionally this fondness for the $50 word trips the author up, such as when he calls Roman translator Lucius Cornelius Sisenna “otiose”, when he probably means “verbose”. “Otiose” means pointless or futile or, archaically, indolent.

Chrystal’s humorous tales will chime with diverse senses of humour. From the politically incorrect instancing by Greek physician Galen of a man “who thought he was an earthenware pot and was terrified in case he shattered”, to his wry comment on Pliny’s recommending as a good aphrodisiac “rubbing the genitalia with a donkey’s penis plunged seven times into hot oil”. He omits to say if the penis should still be attached to the donkey.

Xenocrates calculated that the number of syllables produced by combining all letters of the (Greek) alphabet was one trillion, two billion. Chrystal’s whimsical gloss: “Mary Poppins would have been impressed.”

When you’re not laughing aloud or cracking a smile, you may just be impressed by how much the ancients knew, even in fields such as psychology which, we often flatter ourselves, is a product of the late Enlightenment.

Encore for Plutarch, describing his biographical subject Democritus, who was King of Macedonia soon after the reign of Alexander the Great: “Learning that his son (Demetrius) was sick, Antigonus went to see him, and met a beautiful woman at his door; he went in, nevertheless, sat down by his son, and felt his pulse. ‘The fever has left me now,’ said Demetrius. ‘No doubt, my boy,’ said Antigonus, ‘I met it just now at the door as it was leaving.”

They don’t teach such diagnostic skill in medical school.

Miracula: Weird and Wonderful Stories of Ancient Greece and Rome by Paul Chrystal, Reaktion Books, $34.99.

Want to see more stories from InDaily Qld in your Google search results?

- Click here to set InDaily Qld as a preferred source.

- Tick the box next to "InDaily Qld". That's it.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence