The silent, deadly epidemic tearing the heart out of our rural communities

There is a killer on the loose in the quiet Queensland country town where Madonna King grew up – suicide. She goes looking for answers that nobody can provide

RAY Brown, OAM, has lost five neighbours over his lifetime from youth suicide.

And he’s now supported his son at three funerals; all of them friends from the same class, at the same school on the Darling Downs, where suicide was the cause of death.

“And it just rips the guts out of you,’’ he says.

Brown was mayor of the Western Downs Regional Council for eight years, between 2008 and 2016. He was a councillor before that – since 1990 – and again after that, until 2020.

And with 30 years at the coalface of policy-making in our rural and regional communities, it’s the struggle so many are having with mental health that continues to keep him awake at night.

He says, in the country, most people have been touched in some way through suicide and the money being spent and the programs being implemented were simply not having an impact.

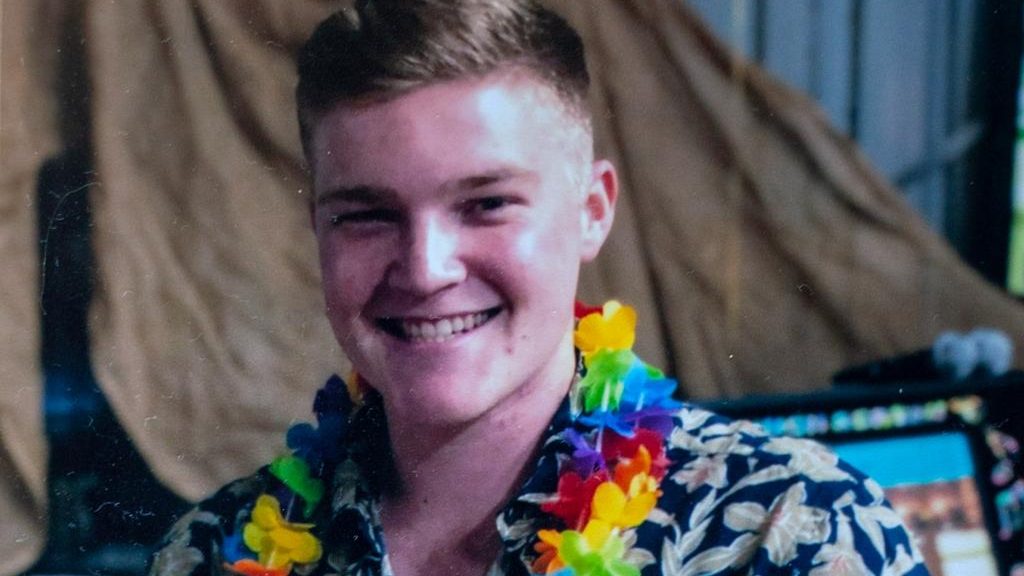

His comments come after reports that seven young people have taken their own lives in Dalby; the town where I grew up, and went to school. One of the most recent of those was handsome 21-year-old Harrison Beil whose sudden death once again rocked the community.

You might like

I called Brown in the hope he could help me understand why. This has been his backyard, until recently, for decades.

But it’s not just Dalby, a point he emphasises, and we have to stop seeing these reported deaths in isolation; as single one-off tragedies.

A new report released last month found that one in 12 Queensland farmers had attempted suicide or self harm over the past five years.

And about 30 percent reported a decline in their mental health over the past few years.

That National Farmer Wellbeing Report found nearly half of Australian farmers have felt depressed, with almost two-thirds or 64 percent experiencing anxiety. For 14 percent of those, it was frequent.

Natural disasters. COVID. A sense of isolation. Unpredictable weather. Children venturing off the land. Feeling forgotten by Government. All those impact on our country cousins – but recent suicides by young people perhaps point to a need for us to address this issue with greater urgency.

The National Rural Health Alliance, two years ago, warned that the greatest increase in suicide rates over the previous decade were in those aged 85 and over, and those 15-24 – and that rates of suicide had increased “aligned with levels of remoteness’’.

“It has been understood for several decades that there is a ‘ripple effect’ in young people, in which suicide tends to appear in clusters of young adults who share social networks,’’ the National Rural Health Alliance reported.

Stay informed, daily

Increasingly governments have thrown money at programs to stem a tide that should shame us all. But Brown says that might be the wrong focus because it has not made a material impact.

“We have this culture that ‘she’s all right’. Well, it’s not – and until us blokes stop talking about football and cricket and start talking about how we are actually getting on….’’ His voice trails off.

Well-being was not a broken arm or a broken leg. We have to start talking about broken minds, and how they can be fixed.

“Who thinks up this idea of youth suicide? As young kids, they see it in their culture around them. That’s what we need to address. Money won’t change that. We have to. People. We need to take ownership of all of this,’’ Brown says.

And in the country, that doesn’t mean fly-in and fly-out counsellors who aren’t prepared to meet locals around their own dinner table.

“In rural and regional areas, the safest place is at the kitchen table, in your own home. They only want to tell their story once.’’ A simple move, that might just make a difference to one family.

Brown says the mental health of countryfolk will be his focus until the day he dies. Asked where he would start, he says the development of greater resilience for our children to navigate rejection is vital.

He’s right. Every expert in this area will call failure the first step on the road to success, but how often – as parents – do we really hope our children never fail; that they win whenever they can?

“They don’t all have to be CEOs,’’ Brown says. “And we all have road blocks right through our lives. It’s how we get through those road blocks. You might have a few scratches.’’

But that might just mean you need to ask for help.

Wise words. So how, as a community, do we use them as a springboard to curb a national tragedy, unfolding while we watch?