Brisbane researcher tackles reef crisis with world-first restoration tech

Queensland University of Technology researcher and marine scientist, Brett Lewis, credits his passion for environmental protection to watching David Attenborough documentaries as a child. He is now leading a team that will help repair some of the damage outlined in Attenborough’s latest film Ocean.

With trawling, blast fishing and rising ocean temperatures killing reefs, including the Great Barrier Reef, Lewis worked to develop a way to help coral regenerate.

“The opportunity to be a person that is just one cog in amongst many, helping to keep these environments as safe and sustained as possible, to help restore them back to some ecological function, resonates with that little boy inside,” Lewis said.

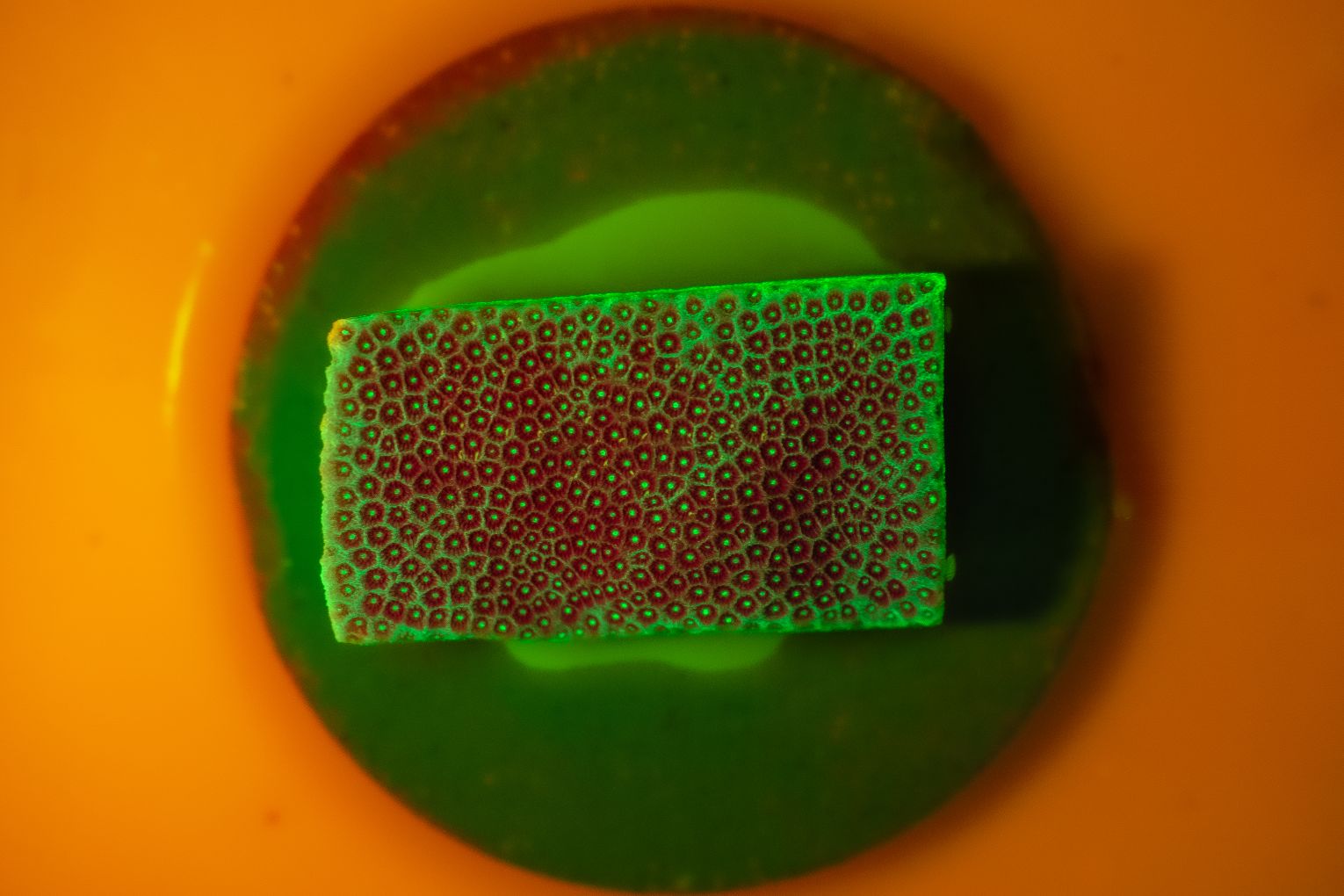

The team has been developing a range of bio-mesh materials and adhesives designed to help stabilise injured reef networks while supporting coral regrowth.

From plastic replacements to sticky, plant-based biomaterials, the bio-mesh offers differing degrees of impact to be used for a variety of restoration and regrowth-related purposes. Many ocean restoration methods use less sustainable materials, making bio-mesh a next-step alternative.

He’s now working with the Australian Institute of Marine Science to take the project international.

You might like

Eco-friendly, cheap and accessible

Lewis and his team are prioritising three key features to create a solution that is eco-friendly, cheap and available.

Because over 75 per cent of the world’s coral reefs are located off the coasts of developing island nations, accessibility has become an integral part of the mission.

“Our restoration programs, which are growing massively across the world, won’t have as big a negative impact, making their efficiency of the program much better because you get more restoration with less impact on the environment,” Lewis said.

Mostly made of waste and plant-based materials, the bio-mesh materials are a cheaper and more accessible option for ocean reef rehabilitation.

A leading coral reef restoration company, MARS, has been deploying and testing the bio-mesh and adhesives in conjunction with their own MARRS Reef Stars, hexagonal steel structures which provide a stable base for coral regrowth while also providing protection. Used together, the two innovations help facilitate growth and marine life regeneration.

Stay informed, daily

Invalid YouTube URL

“We are working with Mars Sustainable Solutions for the restart program to help improve their efficiency, and if we can improve their efficiency, then we can make it more available to a broader community,” Lewis said.

This project began development in 2020 with the Reef Restoration Adaptation Program, headed by Professor Leonie Barner.

Two years ago, Lewis joined the team, hoping to scale the bio-mesh to international reefs. He took a particular interest in helping areas affected by blast fishing – using explosives to stun fish – like Indonesia and Malaysia.

What’s Next?

Lewis said ocean restoration work is done incrementally in “generations” and his team – “Generation Two| – is now responsible for examining the efficiency of their technologies while reducing their carbon and plastic footprint.

“Simply put, the less negative impact we have, the more positive impact we’ll make,” Lewis said.

The next step for Lewis and his team is to continue scaling the bio-mesh and adhesives for international use.

The team has plans for pilot studies in Makassar, Indonesia, and Hope Reef and Pom Pom Island in Malaysia, as well as the Great Barrier Reef.

“What we can do is give it an opportunity to regrow in a way that made the Great Barrier Reef so iconic as one of the most diverse and beautiful ecosystems on the planet,” Lewis said.

“It’s still degrading, but fingers crossed, when the time comes and it can start bouncing back, it’ll do so rapidly.”