Despite all the circumstances, these two posties had the write stuff

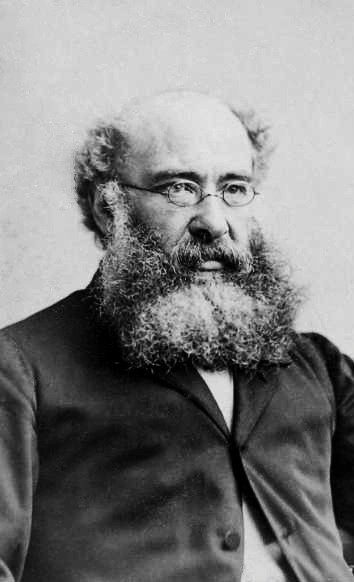

Brisbane writer David Cohen invokes the ghost of English writer Anthony Trollope as he compares himself unfavourably to that prodigious writer.

If you really want to feel inadequate as a writer, I highly recommend reading An Autobiography (1883) by celebrated 19th-century English novelist Anthony Trollope.

It’s one thing to be prolific, but Trollope didn’t just crank out books (The Way We Live Now, Chronicles of Barsetshire, the Palliser novels, etc) at an alarming rate. He did it while holding down a full-time job with the post office.

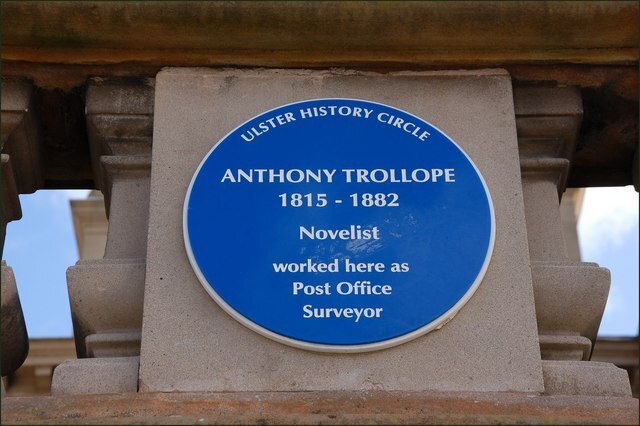

Unlike other novelist-cum-postal workers – your Faulkners, your Bukowskis, your David Fosters – Trollope took his job with the British Post Office at least as seriously as he took his literary endeavours. After a lengthy and unpromising clerkship he was promoted to the position of surveyor and worked hard to reform the postal service, of which he wrote: “I became intensely anxious that people should have their letters delivered to them punctually.”

It was Trollope who recommended the introduction of pillar boxes to Great Britain in the 1850s.

He opines early on in his autobiography that “the vigour necessary to prosecute two professions at the same time is not given to every one”.

As a fiction writer with a day job, I can’t help but wonder how Trollope, were he alive today, would rate my performance.

You might like

As it happens – and perhaps this is why I can’t help feeling competitive when it comes to Trollope – my first job was with the post office. I was 16 when I landed a casual role with Australia Post, where I quickly became known for not introducing pillar boxes to Australia, and for making letter delivery slightly less punctual.

Trollope’s post-office career lasted 33 years. I quit after a few months. I’ve had many different jobs over the subsequent decades, but I can’t honestly say that I’ve prosecuted any of them with the vigour that Trollope applied to his postal work.

As for his writing career – by the time he died at the relatively young age of 67 Trollope had published 47 books, 22 of them while working for the post office. In his autobiography, he modestly estimates that his books “are more in amount than the works of any other living English author”, but hastens to point out that quantity doesn’t necessarily equate to literary excellence.

How do I measure up? In terms of books published, Trollope is currently beating me by 43. Even adjusting for literary excellence, my four books pale in comparison. Can I publish another 44 books by the time I’m 67 (I’m well into my 50s), thereby gaining the lead by one? Time will tell.

Which brings us to the question: How did Trollope manage to produce so much? Annoyingly, it was through hard work and self-discipline. He lived by the motto nulla dies sine linea (no day without a line), rising at 5.30am without fail and writing for three hours, 250 words every quarter hour. That’s 10 pages a day, every day.

I get up only half an hour later than he did, but I don’t produce anywhere close to 10 pages a day. The thing is, I don’t have three hours at my disposal – more like an hour and a half. I suppose I could rise 90 minutes earlier, but what sane person gets up at 4.30 in the morning?

And, as Trollope points out, while three hours a day is sufficient, one must work continuously and not “sit nibbling [one’s] pen, and gazing at the wall”.

Alas, nibbling at my (metaphorical) pen and gazing at my (literal) wall is something I do quite a lot of, whereas Trollope spent his three hours diligently putting words on paper, thereby maintaining an average of about one book a year for most of his life.

Subscribe for updates

(Another curious Trollope/me connection: in 1871 during an extended Antipodean tour, he visited “the very little known territory of Western Australia” where, almost 100 years hence, I would be born and briefly deliver mail.)

Trollope scorns the notion of the writer as some sort of creative artist. To him, a writer waiting for “inspiration” is no less absurd than a shoemaker doing the same thing.

Trollope is quite fond of comparing writers to shoemakers: “A shoemaker when he has finished one pair of shoes does not sit down and contemplate his work in idle satisfaction.”

No, he gets on with the next pair of shoes. And that’s exactly what Trollope did – except with books rather than shoes.

I can’t help but conclude that, by his standards, I’m a bit of a slacker.

But do I feel disheartened? Do I now want to give up writing fiction or, at least, reading autobiographies? On the contrary, Trollope has inspired me to use my time more productively, rather than bemoaning not having enough of it.

His autobiography is nothing so much as a self-help manual for writers – and, to a lesser extent, postal workers.

It may yet spawn a series of motivational books (The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Trollope) or a new app featuring a Trollope-esque voice incanting nulla dies sine linea while I’m in a deep sleep, which I will often be, having risen at 4.30am.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence