‘Cosmic clock’ of tiny crystals reveals the rise and fall of our ancient landscapes

Australia’s iconic red landscapes have been home to Aboriginal culture and recorded in songlines for tens of thousands of years. But further clues on just how ancient this landscape is come from far beyond Earth.

Australia’s iconic red landscapes have been home to Aboriginal culture and recorded in songlines for tens of thousands of years. But further clues on just how ancient this landscape is come from far beyond Earth: cosmic rays that leave telltale fingerprints inside minerals at Earth’s surface.

In our new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, we show how this “cosmic clock” uncovers the evolution of rivers, coasts and habitats.

It also shows how giant mineral deposits formed. Products from these deposits end up in everyday ceramic objects – but carry a hidden landscape story.

Looking through deep time

Earth’s surface is constantly changing as the opposing forces of erosion and uplift compete to sculpt the landscape around us – one example of this is mountains rising, then being worn down by weathering.

To understand today’s environments and predict their response to future change, we need to know how landscapes behaved through deep time – millions to billions of years ago.

Until now, directly measuring how ancient landscapes changed has been a big challenge. A new technique finally gives us a window into the distant past of Earth’s surface.

An ancient Australian landscape shaped by millions of years of slow erosion, Kalbarri National Park, Western Australia. Picture: Maximilian Dröllner

By drilling straight down into the subsurface, we recovered samples that reveal ancient beaches fringing the Nullarbor Plain in southern Australia.

Now located more than 100 kilometres from the ocean, these buried shorelines record extraordinary transformations of the landscape. It was once a seabed, later a woodland with giant tree kangaroos and marsupial lions, and today is one of the flattest and driest places on Earth.

These ancient beaches contain unusually high amounts of zircon, a mineral loved by geologists because it is a sturdy time capsule. Inside these tiny crystals, about the width of a human hair, lies a cosmic secret.

Hunting for cosmogenic krypton

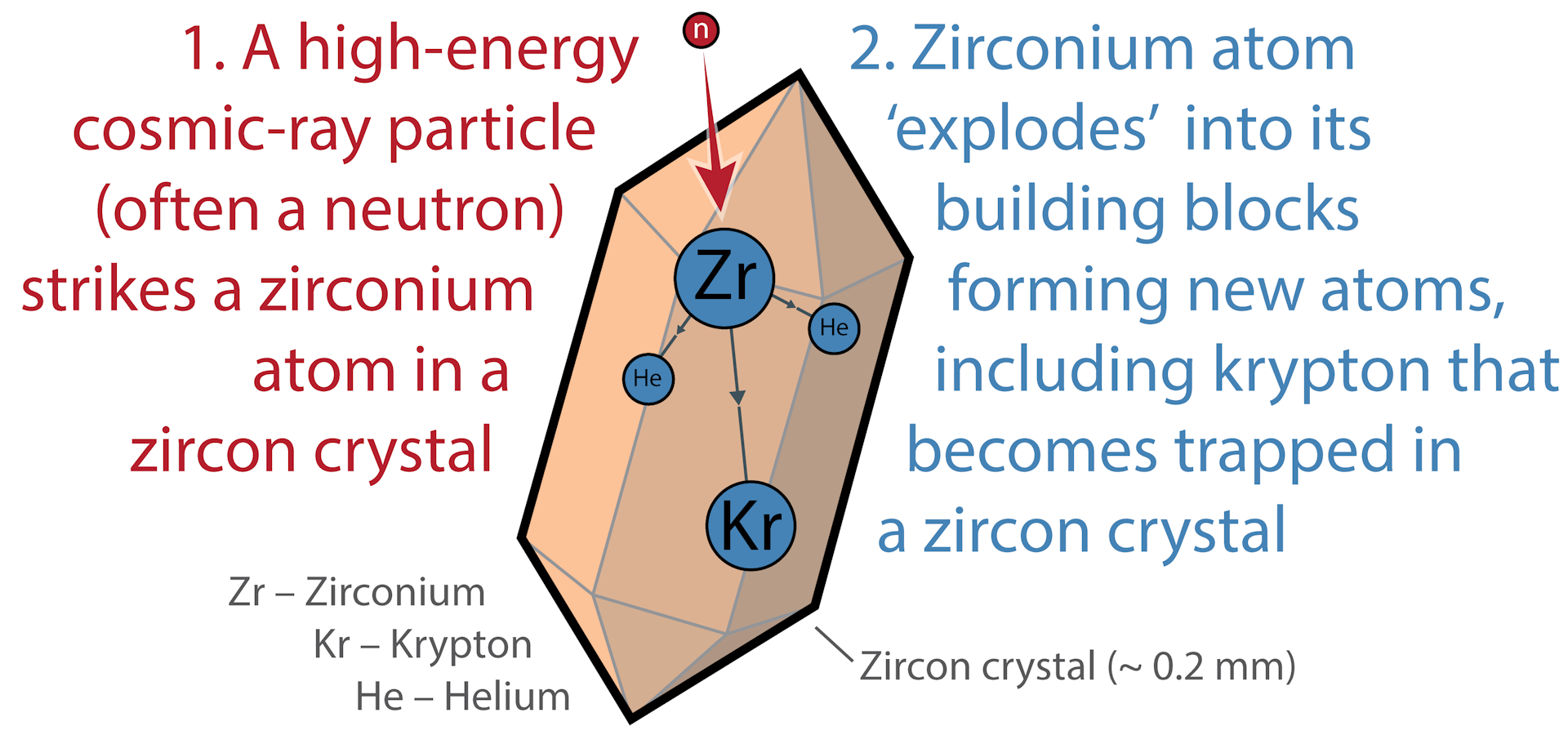

Earth is constantly bombarded by cosmic rays – high-energy particles from space produced when stars explode. Unlike larger meteorites that hit our planet, cosmic rays are smaller than atoms. But when they strike atoms within minerals near Earth’s surface, the microscopic “explosions” produce new elements, known as cosmogenic nuclides.

Measuring these nuclides is a popular way to work out how quickly landscapes change. But many nuclides are very short-lived, making them unsuitable for understanding ancient landscapes.

For our measurements, we used cosmogenic krypton stored inside naturally occurring zircon crystals. This technique has only recently become possible thanks to technological advances. It works because krypton does not decay but preserves information for tens or even hundreds of millions of years.

Simplified sketch showing how cosmogenic krypton is produced and trapped inside a zircon crystal. Picture: Maximilian Dröllner

To unlock this “cosmic clock”, we used a laser to vaporise several thousand zircon crystals and measured the krypton released from them. The more krypton a grain contains, the longer it must have been exposed at the surface before getting buried by younger layers of sediment.

A remarkably stable land

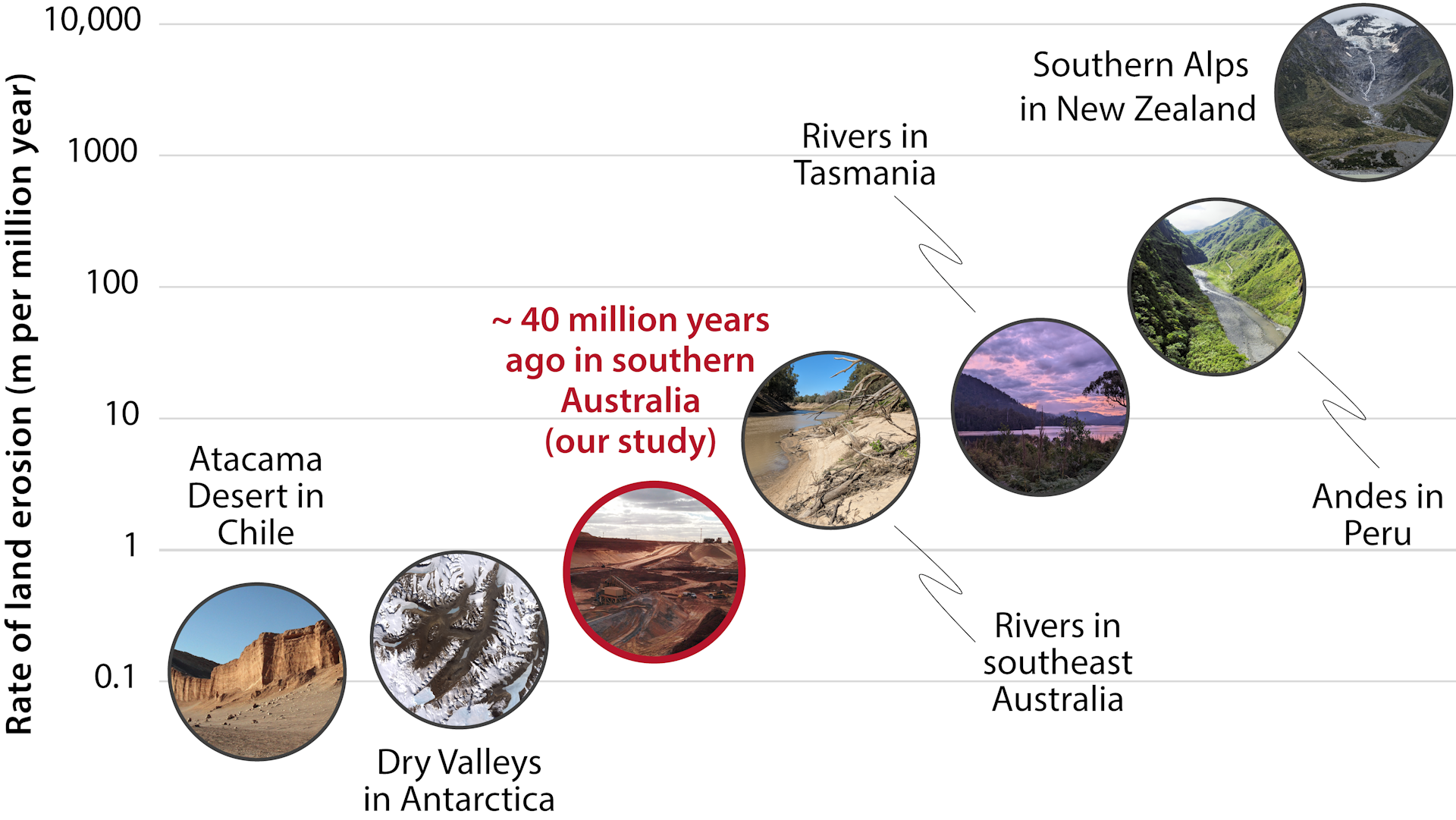

The results show that around 40 million years ago, when Australia was warm, wet and covered by lush forests, landscapes in southern Australia were eroding extremely slowly – less than one metre per million years.

This is far slower than in mountain regions such as the Andes in South America or the Southern Alps in New Zealand. However, this rate of erosion is similar to some of the most stable regions on Earth today, such as the Atacama Desert or the dry valleys of Antarctica.

Comparison of our erosion rate estimates (a key measure of landscape change) with other Australian and global landscapes, highlighting the very slow rates of landscape evolution. Picture: Maximilian Dröllner

We calculated that the zircon-rich beach sands took about 1.6 million years to move from their place of erosion to a final burial site on the coast. During this very slow sediment transport, many less durable minerals were gradually broken down or dissolved by weathering. What remained were the most resilient minerals, such as zircon, which became progressively concentrated.

Over time, this natural filtering process produced beach sand deposits very rich in economically valuable zircon and other stable minerals.

The results also capture a turning point in the region’s landscape evolution. After a period of relative stability, a shifting climate, Earth movements and sea levels triggered faster erosion. The sediments started to move faster as well.

A new crystal clock

This “cosmic clock” helps explain the mineral wealth along the edges of the Nullarbor Plain, including the world’s largest zircon mine: Jacinth-Ambrosia. This mine produces about a quarter of the global zircon supply.

A lot of zircon is used in ceramics manufacturing, so chances are high many of us have already had contact with these minerals that spent far longer at Earth’s surface than our own species has existed.

A sweeping view across the worlds largest zircon mine. Picture: Milo Barham

By reading cosmic ray fingerprints in zircon, we now have a new geological clock for measuring ancient processes on our planet’s surface.

Investigating modern landscapes, where surface processes can be measured independently, will help refine and broaden its use – but the potential is enormous. Because krypton and zircon are stable, the technique can be applied to periods of Earth history hundreds of millions of years ago.

This opens the possibility of studying landscape responses to some of the biggest events in Earth history, such as the rise of land plants about 500–400 million years ago, which transformed the planet’s surface and atmosphere.

To do this, we could analyse zircon crystals preserved in river sediments from that time, likely allowing us to measure how strongly the arrival of land plants reshaped erosion, sediment transport and landscape stability.

Earth’s landscapes hold memories trapped in minerals formed by cosmic rays. By learning to read this “cosmic clock”, we’ve found a new way to understand the history behind iconic landscapes. Perhaps even more importantly, it provides a blueprint for the changes that may lie ahead.

Maximilian Dröllner, Adjunct Research Fellow, School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University; Georg-August-Universität Göttingen ; Chris Kirkland, Professor of Geochronology, Curtin University, and Milo Barham, Associate Professor, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Want to see more stories from InDaily Qld in your Google search results?

- Click here to set InDaily Qld as a preferred source.

- Tick the box next to "InDaily Qld". That's it.