New research into reef’s coral-eating starfish problem

One of the largest-ever marine conservation initiatives helped prevent frequent outbreaks of a coral-eating starfish on the Great Barrier Reef, new research has found.

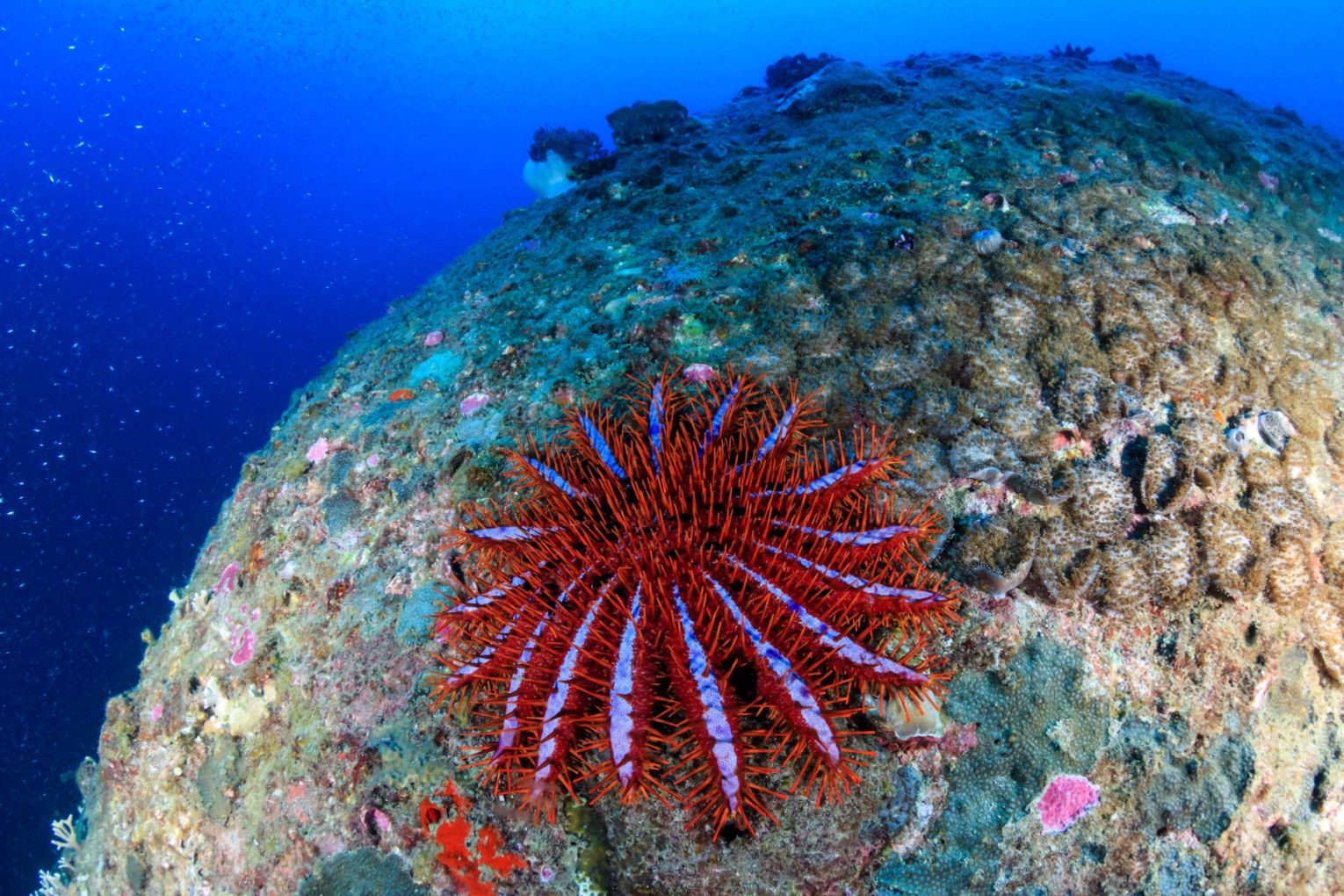

A CSIRO and the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) study has found that proper zoning and fisheries management strategies had a beneficial impact on crown-of-thorns starfish (CoTS) outbreaks on the Great Barrier Reef.

The study proved that management strategies implemented in 2004 likely played an important role in recovering fish populations in the marine environment.

Dr Scott Condie, CSIRO researcher and lead author, said CoTS are one of the biggest causes of coral death on the Great Barrier Reef, with multiple outbreaks occurring over the last forty years.

“Particular fish, like emperors, eat crown-of-thorns starfish. Protective measures, such as increasing no-take zones to 33 per cent, and tighter fishing regulations, were put in place in 2004 to protect these predatory fish,” Dr Condie said.

Dr Condie explained that these initiatives likely averted a catastrophic tipping point that would have left the GBR with less large fish and substantially less coral.

“Long-term monitoring shows that the frequency of outbreaks across the Great Barrier Reef is consistently lower in protected zones,” Dr Condie said.

As a natural predator of coral, population outbreaks of CoTS can cause widespread coral loss, having a significant impact on the health of the GBR.

Dr Daniella Ceccarelli from AIMS said the fact that these protective measures have been working highlights the need for ongoing management and long-term monitoring.

“Model projections to 2050 show that without these fish protection strategies, there could be a four-fold increase in the percentage of reefs with CoTs outbreaks,” Dr Ceccarelli said.

Stay informed, daily

Dr Ceccarelli said without intervention, grouper and emperor populations would have consistently declined on the GBR under increasing fish pressure.

“This modelling is an important step towards understanding the potential for crown-of-thorns starfish management to protect the Great Barrier Reef under the increasing threat of climate change,” Dr Ceccarelli said.

The study also looked into the benefits of direct CoTS management on the GBR, which has grown from manual removal in the 1980s and intensive culling at tourism sites to the current CoTS Control Program delivered by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Want to see more stories from InDaily Qld in your Google search results?

- Click here to set InDaily Qld as a preferred source.

- Tick the box next to "InDaily Qld". That's it.