How curator Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow helped shape GOMA’s landmark Olafur Eliasson exhibition

As GOMA prepares for the December unveiling of Olafur Eliasson: Presence, curator Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow reflects on the years of dialogue, planning and experimentation that have shaped one of the gallery’s most ambitious exhibitions to date. Her curatorial relationship with the acclaimed Icelandic–Danish artist includes time spent inside his Berlin studio – a place where ideas gather and artworks evolve through conversation as much as through making. Now, as Olafur Eliasson: Presence prepares to transform GOMA’s entire ground floor, Geraldine shares the thinking, collaborations and studio insights that have guided its development, offering a rare glimpse into how an exhibition of this scale comes to life.

The idea for Olafur Eliasson: Presence took root after GOMA’s Water (2019) exhibition, where Eliasson’s work featured prominently. How did that earlier collaboration and dialogue with the artist lead to this new exhibition?

Olafur created Riverbed as a site-specific work for the Louisiana Museum in Denmark – I don’t think he expected an invitation to present it again on the other side of the world in Brisbane. I think he appreciated our ambition and how relevant it was to this completely different context – we really enjoyed working together. Our director, Chris Saines, and I felt this would be a great basis for a future exhibition. Water ended up closing early due to COVID, but with the world shifting to a different rhythm, Olafur and I came to talk regularly. He’s a night owl, and we came to enjoy our slow, circular and quite philosophical conversations.

You spent several months working within Olafur Eliasson’s Berlin studio during your curatorial residency. What was that experience like on a day-to-day level, and how did working so closely with the studio team help shape the kind of experience audiences will have at GOMA?

It was really special to be trusted to join Olafur’s team for such an extended period – not just a meeting or two, but to really have open access to meet people, learn about their work and participate in the life of the studio. The studio kitchen is renowned; it truly brings everyone together to enjoy delicious locally sourced vegetarian meals. Olafur and his team have a genuine interest in hospitality, nurture and care. These ideas were at the centre of our first formal meetings about the exhibition. We sought to place them at the centre of our audience’s experience of the exhibition – both in terms of which artworks we might feature and the ideas driving new work being tested and developed for Brisbane.

What stands out to you most about Olafur Eliasson as an artist and thinker, having worked so closely with him over several years?

I wasn’t expecting how much space Olafur gives to emotion and interpersonal care. I knew the studio had a really strong intellectual, experimental and ideas-driven culture; I knew Olafur as an advocate for awareness and action on climate and environmental issues. Olafur really loves what he does and is very good at enabling the people who join him to extend the reach and ambition of what he makes. Many key members of his team have been with him for two decades. It’s incredible to see him quickly move between different projects, different modes of thinking and making with such ease. And a joy to see the place drawing has in his thinking, as well as how much pleasure he gets from the process of making art. I think we feel this when we experience his work.

Olafur Eliasson: Presence is one of GOMA’s most ambitious exhibitions, taking over the entire ground floor. How would you describe the experience visitors can expect when they step inside?

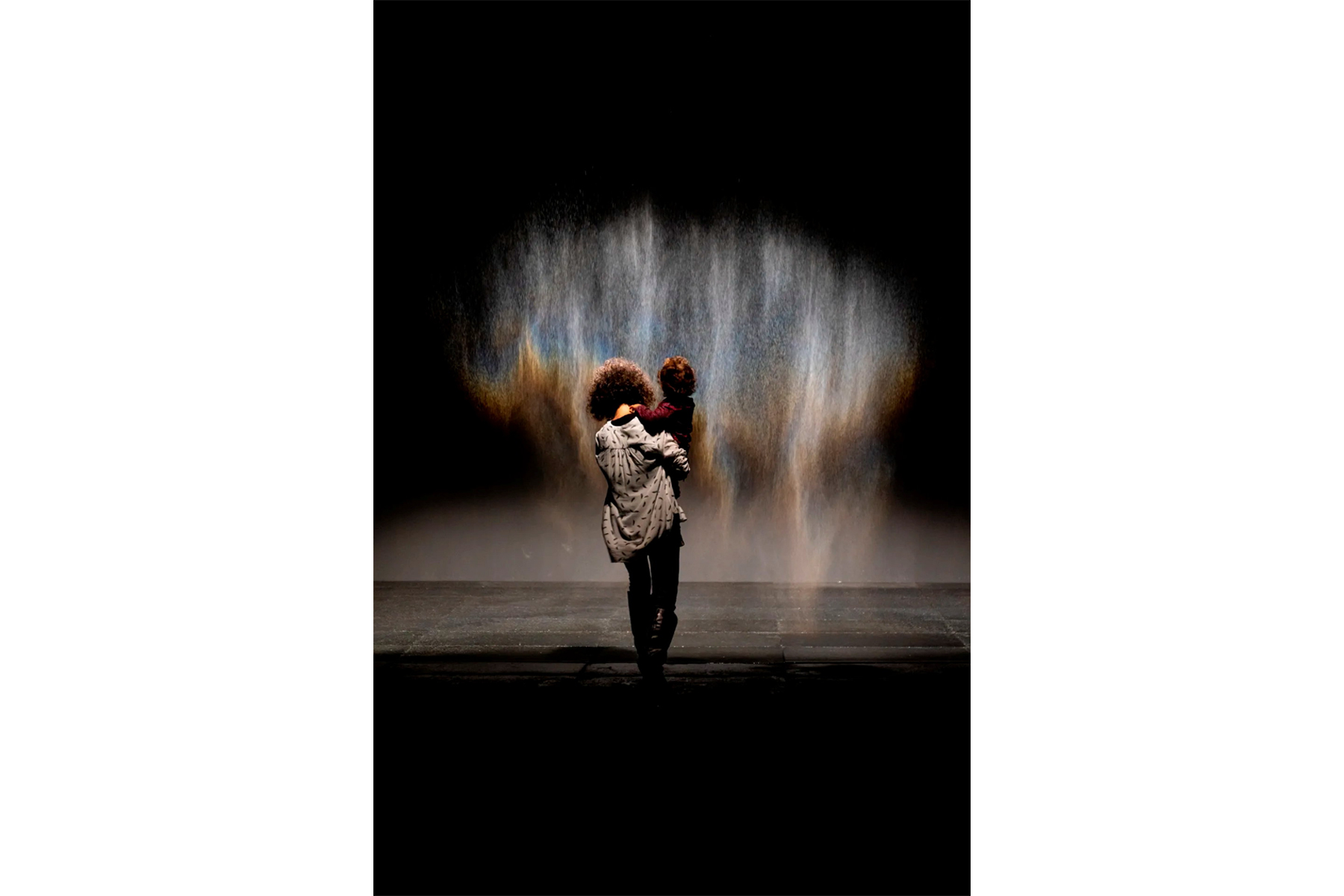

Leaving the humid heat of the Brisbane summer, our visitors will initially step into views of Iceland. Olafur has photographed and taken inspiration from Iceland over the course of his career – the land of his parents and ancestors. After this first gallery, there is a sequence of large immersive installations, including three new works made especially for Brisbane and one of Olafur’s most iconic early experiential pieces, Beauty (1993), which we are thrilled to have brought into the collection. This exhibition is like a Tardis – full of surprises. What you see or perceive will constantly change, and the space stretches in unexpected ways as you move further into it.

You’ve said that “tenderness and care” were the two words that guided your dreams for this exhibition. How did those concepts influence the way the exhibition was imagined and realised?

I created a spreadsheet of works we were considering and the ideas I felt they conveyed – I often do this. At times, these qualities of tenderness and care weren’t as present as I hoped; there’s always a lot to keep track of and question. So I thought about which works we could add to convey these ideas more clearly. Iceland series #8 shows a landscape which, for me, seems to ‘hold’ a rainbow with tenderness; the Small cloud series also conveys this, where we see a little arched cloud come into being. Other works seem very spectacular or optically driven at first – such as Presence (2025) and There are no bad parts (2025) – but they too connect to how we care for ourselves and each other. Some of the newest works, such as Presence, are so ambitious they haven’t been fully realised before, just partially tested in the studio. While these ideas have driven their creation, the excitement will be discovering what we actually feel in the presence of these new works.

New installation Presence (2025) will fill the gallery with golden light, echoing Olafur Eliasson’s iconic The weather project at Tate Modern. What makes this new work such a powerful centrepiece for the exhibition?

The weather project is one of Olafur’s most cited works; he has declined every subsequent invitation to present it again. He used the great height of the Tate’s Turbine Hall, covering the ceiling with mirrors and installing a flat half-sphere that visitors perceived as a full sun. It was a work that not only played with perception but brought people together in a way that allowed them to see themselves as a community – an experience of ‘we-ness’, as Olafur calls it. Presence has similarities, but it will exist in three dimensions rather than as a flat form, and the ‘sun’ will appear to move as we move. It is incredibly ambitious, developed through long periods of thinking, conversation and testing in the studio. I think people will feel as if they are walking through space, able to walk close to the sun, and see themselves reflected many times over. Olafur is as interested in how we understand ourselves as he is in how we relate to each other. It promises to be a startling and surprising work.

Riverbed (2014) – a rocky landscape complete with a flowing stream, first presented at QAGOMA in 2019 – returns for this exhibition. Why did now feel like the right time to revisit this work, and what new relevance or resonance does it bring today?

When we first presented Riverbed, Queensland was substantially in drought; Australia then experienced terrible bushfires and subsequent floods. As an artwork and experience, it offers an incredible lens through which to consider how precious water is, and the long cycles of time and evolution we are part of. We acquired Riverbed for the gallery’s collection – a mark of just how ambitious and unique QAGOMA is. Bringing it back now allows us to share more of how it relates to Olafur’s Icelandic heritage. For him, this is also what remains as the ice melts and glaciers retreat. Like Australia, Iceland is experiencing enormous climatic changes – the impacts of which are clear in Olafur’s photographic series Glacier melt (1999/2019). How do we move from seeing and feeling these changes to acting? What can we do, how can we work together creatively, playfully and with hope? I’ve placed this photographic series alongside a fantastic collection of models and studies from the studio, Model for a circular city. Visitors can then make their own dream city in white Lego via another iconic work from the collection, The cubic structural evolution project (2004).

After so much time surrounded by Olafur Eliasson’s explorations of light, perception and nature, what lingers with you personally when you step outside the exhibition space?

Within the exhibition are entirely new works using the polarisation of light, where what we perceive changes completely as we move. What was initially black becomes white; what was in full colour becomes entirely transparent. After experiencing these works in development, I am now looking forward to seeing them fully realised at GOMA. I feel a heightened sense of how strongly what we see and understand of the world depends on where we stand – and that this shifts in surprising and beautiful ways.

Finally, what do you hope audiences in Brisbane carry with them after experiencing Presence?

A sense that we can surprise and know ourselves in new ways. A sense of energy, light and hope.

Olafur Eliasson: Presence runs at GOMA from December 6, 2025 to July 12, 2026. Book your tickets here.

This article was written in partnership with our good friends at QAGOMA.

Want to see more stories from InDaily Qld in your Google search results?

- Click here to set InDaily Qld as a preferred source.

- Tick the box next to "InDaily Qld". That's it.